Clueless Investing vs. the Internet

- Markets are conversations.

- Markets consist of human beings, not demographic sectors.

- The Internet is enabling conversations among human beings that were simply not possible in the era of mass media.

- Hyperlinks subvert hierarchy.

- In both internetworked markets and among intranetworked employees, people are speaking to each other in a powerful new way.

- These networked conversations are enabling powerful new forms of social organization and knowledge exchange to emerge.

- As a result, markets are getting smarter, more informed, more organized.

- Participation in a networked market changes people fundamentally.

- What's happening to markets is also happening among employees. A metaphysical construct called 'The Company' is the only thing standing between the two.

- Companies can now communicate with their markets directly. If they blow it, it could be their last chance.

- Brand loyalty is the corporate version of going steady, but the breakup is inevitable – and coming fast. Because they are networked, smart markets are able to renegotiate relationships with blinding speed.

- Networked markets can change suppliers overnight. Networked knowledge workers can change employers over lunch. Your own "downsizing initiatives" taught us to ask the question: "Loyalty? What's that?"

- Today, the org chart is hyperlinked, not hierarchical. Respect for hands-on knowledge wins over respect for abstract authority.

- We want you to take 50 million of us as seriously as you take one reporter from The Wall Street Journal.

- To traditional corporations, networked conversations may appear confused, may sound confusing. But we are organizing faster than they are. We have better tools, more new ideas, no rules to slow us down.

- We are waking up and linking to each other. We are watching. But we are not waiting.

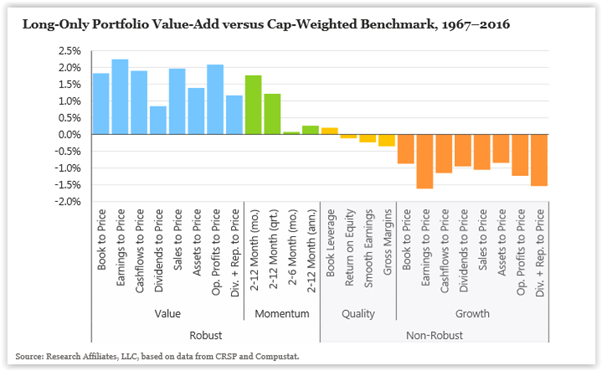

- Value stocks will typically trade on low valuation multiples (like price/earnings and price/book);

- Momentum stocks will typically be trending strongly higher in price, irrespective of which sector they belong to;

- Quality stocks will have robust and well recognised businesses and brands with global reach, with a history of strong and uninterrupted dividends;

- Growth stocks will be displaying strong growth in revenues (if not necessarily profits or dividends) and will often be in the technology sector.

Email us

Email us