Luxury and power on steroids

Snail mucus, ancient Yuan-Dollar weights, and a giant gold statue in Nashville

The BRITISH MUSEUM's summer 2023 exhibition Luxury and power: Persia to Greece opened in May to rave reviews.

Supported by BullionVault and running until mid-August, it brings together stunning objects beautifully crafted from gold, silver and glass over 2,000 years ago to show how ideas of luxury and power in Ancient Persia – then the largest empire ever known – crashed into Ancient Greek culture after Athens, Sparta and Greek city states won a series of surprise victories over those invaders in the early 5th century BC.

Why this collection, from that period of history, with these themes, and why now? Adrian Ash, director of research at BullionVault, speaks here with Jamie Fraser, curator at the British Museum for the ancient Levant and Anatolia and also lead curator of the exhibition.

Adrian Ash: Thanks very much for your time today, Jamie. In a nutshell, what's Luxury and power: Persia to Greece about? What story does it tell?

JF: What this exhibition does differently to a lot of other British Museum exhibitions is that it's taking a concept, and here that is the concept of luxury and how it intersects with political authority. But it's not telling just one story, it's telling multiple versions of the same story stretched all the way across from south-eastern Europe, all the way through the Middle East and into Central Asia.

How do luxury and political power relate? These expressions and relationships are very different depending on whether you are, you know, in democratic Athens or in the kingship of ancient Persia.

That 'Greek West' and 'Persian East' idea forms the crux of this show. Through the lens of luxury, we're looking at how the Persian court used luxury to perpetuate, to legitimate, and to strengthen imperial control throughout what was the largest empire the world had ever seen to that point. But we're also looking at how we have inherited Greek ways of looking at this, because here in the West we really do look at the Persians through the eyes of their arch rivals – their arch nemesis – the Greeks.

That's because we've inherited Greek history and not really Persian history. And of course the Greeks look at Persian luxury and go 'Well, no wonder we beat them in the Greek-Persian wars. These Persians had become weakened and corrupted and feminised by this cancerous form of luxury.'

Of course, it isn't doing that. Luxury is a very sophisticated tool in the Persian court. But also what the Greeks tell us about themselves – that they're not luxurious, that they're all plain-living, simple-living – well, that's a bit of an idealistic furphy as well, because those Persian styles of luxury insinuate themselves into Greek lifestyles and in some really surprising ways. And then Alexander the Great comes onto the scene, and the relationship between luxury and power is renegotiated again.

So that was a very long answer to the question! But that, in a nutshell – which is what you asked for! – is what is Luxury and power is about. It's looking at how things are used to give social prestige and political prestige across a multitude of different cultures in the ancient world.

AA: So this is, what – we're in the 5th, 6th century BC, and we are in a period where displays of wealth and ceremony I guess are very much part of how political power operates, right?

JF: Yeah, so the Persians really kind of charge out of the highlands of south-western Iran in the mid-6th century, and punch their way right across through Central Asia into the Anatolian Plateau and parts of North Africa, particularly Egypt. This is a huge linguistically and culturally diverse empire, it contains a multitude of different cultures and of different languages. And what the Persians were really good at, is the Persian king was using luxury in a way that all the local rulers representing his authority – whether it's on the Armenian hinterland or the Turkish coast or the Nile Valley – they can all use these sorts of luxurious goods in the same way. The paraphernalia of luxury becomes kind of an aesthetic lingua franca that's uniting the whole empire, so it's creating a language of stuff that the ruling elite can use no matter where they are, to kind of opt into the imperial political system. And it's a very powerful, very sophisticated and very successful tool.

AA: And in this universal language of luxury and power, precious metals play a key role?

JF: Absolutely – precious metals are fundamentally important on a number of different levels.

In part, it's how they're used. One of the key kind of vessel types that we've got in the exhibition and that we have in the Persian world are called rhytons or rhyta. These are, well, imagine kind of a large Viking-shaped drinking horn on one side, but you don't drink out of these. On the opposite side, the opposite lower end, is usually a spout crafted as a fantastic beast, like a griffin or a lion or a bull, and wine would flow out of a spout on that animal, flowing into a gold or silver bowl, and you would drink out of the bowl.

It's a very theatrical way of dining, very ostentatious, which the Persian king would use when he is at court with various dignitaries or guests, and it's a way of him showing the prestige of all the resources that he has, bestowing prestige upon the king. But the king also bestows his own prestige upon these objects, and that's really important, because at the end of the feast he gives out these objects as largesse, as generosity. So long after the king has moved away, or when people take these objects back to their local courts, they do the same thing. Which means when we're talking about luxury in ancient Persia that we're talking about luxuries, about luxurious goods and objects. It's very clear in this style, this court style. It's the stuff the King uses, and metal vessels are absolutely key because they're transportable and transferable. And what's particularly important about them is that they're made to specific weights.

We know this because we have weighed all of the silver and all the gold Persian or Achaemenid metal vessels we have in the British Museum collection. When I say Achaemenid, that's the name of the ruling Persian dynasty. And these sorts of vessels are all made to certain weights. So it's not only transferring a common style, but it's portable wealth. It's a way of wealth coming in from the edges of the empire to the political centre, and then it's a way for the king to distribute wealth, as he wants to do, from the imperial centre back to the periphery again using largesse and creating these political linkages. It is very much key to the economy as this wealth gets shunted around this highly connected world.

AA: So what we've got with the ancient Persian Empire, the Achaemenids as you say, is soft power – if we can call it that today maybe – through these displays, these ostentatious displays of imperial activity in terms of how they dine and so on. And people I presume, are watching this not quite as a ceremony, but it's theatre, and then there are gifts made of these precious metal objects where the bullion value is actually key.

I want to come back to both of those points in a second. But first, the Persians attempt to invade Greece – or maybe the Greeks just get a bit uppity and start trying to kick them out – and we end up with the Greek city states, who now club together under Athens and actually have a series of quite startling victories against the Persians. And in doing that, they also capture a lot of loot from the battlefield, or rather, from the command tents of the Persian rulers. And this loot is shocking to them, right? I mean, in the historical record, we're told that the Greek commanders are overwhelmed by the kind of wealth and luxury that they find.

JF: Yeah, so the main author we've got for this is Herodotus. He's known as the father of history, but jeez, he was a good storyteller as well. And there's one event that he's crafting, which in this case is the Spartan army's victory leading the Greek forces against the Persians at the Battle of Plataea. This is 479 BC, and it's the major land battle that really kicks the Persians out of the Greek peninsula and then ultimately out of Europe completely.

Herodotus builds this up with his narrator's flair to the moment where the Spartan generals conquer the command tent of the Persian army, and then he describes the electricity with which they discover all this unimaginable splendour, stuff that they can't even conceive of coming from the resource-poor Greek peninsula, and particularly from the austere city of Sparta as well. He describes the sumptuous textile hangings, the gold and silver furniture, the gold and silver drinking vessels, the jewellery that the Persians are wearing, the perfume that they're wearing, the eyeliner that they're wearing. No wonder these Persians lost! They've become women! They've become weakened, they've become effete through this corrupting form of luxury.

Herodotus goes on that the Spartan general then says to the servants who have been left behind by their Persian commanders, 'Make us a meal, as you would for your Persian king. Serve it as you would for your Persian kings.' Then he says to his Greek cooks, 'Now make us the standard sort of meal that we're used to.' And then he brings all of the Greek commanders into the tent and there's this sumptuous feast that the Persians would have eaten with the gold and silver vessels. Then there's, you know, the bread and porridge of the Greek forces, and he says, 'Imagine the hubris of these Persian forces wanting to invade us when they've got so much. And this is all we've got to offer.'

Of course, this is a story very much NOT about Persian wealth. It's much more about Greek discipline and about Greek restraint and Greek simplicity of living, or at least the ideals of that if you believe Herodotus. But the reality is a lot more complicated.

AA: Obviously Sparta is famous for – well, Spartan is the adjective that we use today to describe discipline and meagre rations etcetera. But surely the Greek world must have had some element of luxury. I mean, in terms of the elite within Greece and within the city states such as Athens, there must have been some luxury as part of their soft power, this couldn't have been entirely new to the Greeks when they stumbled upon it. Certainly not the idea of using precious metals?

JF: So in the 6th century BC, the century before the Greek-Persian Wars, Athens at that point is ruled by competing aristocratic clans. And these clans are reaching for the exotica from the east, from the Anatolian kings of ancient Turkey, from ancient Egypt, for ivory furniture inlaid with gold and silver. This is the sort of stuff that they want to trade in, to give them a social edge in this kind of political dance through which these competing autocratic clans are ruling the city.

The scale is significantly smaller. It's nothing compared to the fabulously wealthy Anatolian kings – Midas with the golden cup, for example – or the Persian kings, who become kind of the symbol for all of this. The scale in Athens is very, very reduced. But it is there.

The difference in the 5th century is that around 507 or 508 BC is the starting gun, if you like, where Athens becomes a democracy. Now, the trajectory towards that is very complicated, but ultimately what happens is that Athenian citizens get a vote in political decision making, and it's based upon their citizenship rather than on their inherited wealth or their family name. That's significantly important because it's a real shift in the way politics has been done. This very much arises from political instability in the city between those competing aristocratic clans. So whereas in the 6th century luxury had been quite a positive thing, where those eastern exotica are sought after, in Athens' early democracy, well – if you are being ostentatious with your wealth, if you are reaching for these symbols of luxury, then you're kind of harking back to those pre-democratic days. You're kind of trying to rise above your new democratic station. So to be ostentatious, is to be undemocratic.

Then you throw in the Persian menace. The Persians try to invade in 490 and then they actually capture Athens briefly in 480, 479 BC. And the Greeks come face to face with wealth and spectacular splendour on an unimaginable level. So luxury really does become a dirty word, because not only are you being anti-democratic, but perhaps you're sympathising with the Persians. You're being eastern and autocratic and tyrannical and barbaric. Very un-Greek.

So there's this ideal of being very restrained and very disciplined that's emerging in Greece and particularly in Athens, because of the shape of this new political system. That's the rhetoric, and that's the ideal. But this stuff really still is there, particularly the booty coming off the Persian battlefield. And the way in which that stuff shapes Athenian society around it – well, that's very much the substance of this exhibition.

AA: So the Greeks have now got a real political problem with the loot that they accumulate. I mean, what do they do with all this? Because I'm presuming most cultures in the period in that region, it would have been divided up amongst the commanders, among the elite. But they can't do that.

JF: It's really interesting, because they do do that to an extent, so that some of the commanders and some of the hoplites, some of the soldiers, do get a degree of this loot. Herodotus tells us that it's divided up on certain ratios and so, for the first time, among Greek hoplites. These are the soldiery, the common soldiery, and they are returning with gold and silver vessels which would have been unimaginable before.

So you've got a confrontation between the full range of Greek society, not just the aristocracy, with these sorts of luxurious goods in completely new and unforeseen ways, and that has an effect on how the society engages with this kind of new luxurious landscape at very different levels.

AA: There is some element then of this Persian luxury leaching in, but it's coming further down the social scale as it goes into Athens?

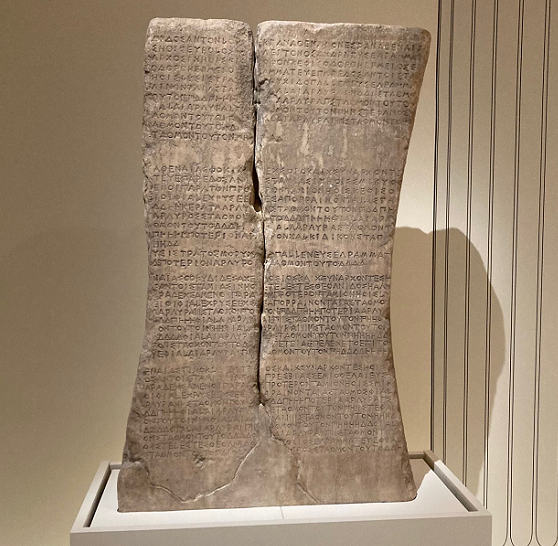

JF: Yes, and you see this happening in two ways. In the first way, the official way, luxury is okay if it goes for the glory of the city and not for the glory of the individual. So from all the loot, a part of it is cleaved off and goes to Athena, the goddess, and it gets stored in repositories, particularly repositories such as the Parthenon, and one of the most interesting objects we have on display in the exhibition is a Greek inscription, and it's one of several stele – sort of inscribed stones – that were erected on the Acropolis and what it is, is basically a very large Excel spreadsheet and it's detailing its listing, all the stuff that's being held inside the Parthenon treasury.

Marble, Athens, Greece 426-412 BC. Photo © Adrian Ash. Courtesy of the Trustees of the British Museum.

Sure, the Parthenon's a religious temple. But what it really is, what it's actually functioning most as, is an imperial storehouse and all the loot in this particular list that we have is the gold and silver vessels. And it's saying, you know, in this particular year, Treasurer So-and-So is handing over to another Treasurer So-and-So. And everyone knows it's ticketty-boo because I'm about to list everything that's inside. We've got 6 silver drinking vessels, 8 gold plates, 9 gilt silver wine rhyta with the heads of animals just as we've seen in the Persian court, all that sort of stuff.

But the kicker, the really interesting thing is they give it their weight, and these are supremely, beautifully crafted objects. Objects that have a kind of a resonance in a Persian setting. But here they've been transformed into something that is bullion. They're there as trophies of the Persian War, but they're there as an imperial treasury to be melted down should the city need them. This collective Fort Knox, if you like, underwrites Athenian wealth.

So that's the official version. But of course, this stuff is still being used in households in a way that is quite destabilising to the political order. We don't know a huge amount about this, simply because in the archaeological record, if you ever go into a museum and you see complete vessels like these, silver and gold vessels, if they're there in a museum, it probably means they've been found inside a tomb. That's because things survive if they've been buried in a tomb. Gold and silverware doesn't really survive if, otherwise, it gets handed down and handed down and eventually melted down and turned into something else. And in the Persian world, a lot of the treasures we have come from tombs in Persia, or from elsewhere in the empire. But the Athenians were really parsimonious with what they buried their dead with. They buried their dead with the bare minimum, and so all the stuff that we think might be there, these precious gold and silver vessels, they didn't survive because they've been melted down at some point.

So there are historical biases with how we look at the Persians, but there's archaeological biases with how we look at the Greeks. So when you go into a museum and you see halls and halls of red figure vases and black figure vases and all this sort of stuff – the stuff that today's classicists wearing, you know, dirty cardigans and unwashed beards get very het up about – well, this is kind of nouveau riche stuff. The real classy stuff was the gold and silver vessels, but they don't survive. And so we don't quite know how they worked in society because we don't have them. It's a really interesting point.

AA: Just going back to the bullion value and the 'Community Chest' of treasure, I think a lot of people, even if they've been to Athens, might not realise that the Parthenon was 'a temple without an altar' as I think you've called it. And it basically functioned as a storehouse – effectively, if I may, a bullion vault and you have these audits, right, etched in stone and saying 'This is what's inside the store house' just as BullionVault today has its daily audit. The vault operators send us the bar list and they tell us the brand of the bars and the bar numbers and the weight and the fineness. And then we can publish that for all of our customers to check...

JF: Nicely put!

AA: But this idea back then was maybe more similar, perhaps, to a central bank today in the sense that this is national treasure. And so there's that really interesting switch that you touched on, which is that whereas the Persians were using this for its luxurious value, Ancient Greece – and, of course, Lydia nearby – was seeing not so much the invention of money per se, but certainly the development and the first real mass adoption of coin. So for me, in the exhibition, something I find really interesting is this idea that these treasures were being stored for their bullion value, and that value was being recorded – the weight and therefore the value – as just a lump of metal rather than as a beautiful object.

This is contemporary with the birth of coined money, which of course is all about counting. The myth of Midas, for instance, is not so much that he's greedy, it's just that everything he touches turns into gold, because now he can buy anything for a certain number of gold coins. How different is that for the Persians? Does that wash back into Persia? And what about the democracy idea? Does that wash back into Persia at all, or does Persia remain all despots and client kings?

JF: I'll come back to the coins in a second, because democracy never really washes back into Persia. But what is interesting about the Greek democracies is that there are certain Greek city states on the Anatolian or the Turkish Aegean coast which were absorbed into the Persian Empire from about 550 BC, give or take. And some of those were democracies. And although they're absorbed in the Persian Empire, the Persian governors let these democracies continue in their local form. Sure, they're under occupation, but they're still democracies for local governance. So when we come to the Persian invasion of Greece, then you get Western thinkers like John Stuart Mill, who in 1842 described the Battle of Marathon – even as an event in British history – being more important than the Battle of Hastings because it was, you know, this moment at which democracy pushed off tyranny and allowed enlightenment and all this to flourish.

Well, that's a bit kind of bollocks frankly, because we don't know how the Athenian democracy would have worked under Persian control, we just don't know. And besides, Sparta is one of the great slave-owning states in history.

AA: Yes, Athens had thousands of helots as well, right?

JF: Yeah. I mean, there's about 50,000 adult male citizens in Athens, all served by about 100,000 slaves. So it's a really interesting kind of juxtaposition. Democracy is, you know, it's a complicated situation and it's not enough to call them one or the other. But no, it never catches on beyond some of the Greek city states.

Coinage, however, does catch on, because once you've invented that concept of a coin, well, that is an irresistible thing that is remarkably sticky. And yes, the first coins that we see are the Darics that come out of Lydia, out of those south-western Anatolian kingdoms. And that does get picked up by the Persian court very strongly, and so it does get transferred throughout the Persian Empire, and then the Persian Empire really is the vehicle by which coined money gets picked up in this one place and punched throughout the rest of the Middle East, Africa and Central Asia. And it's the same thing for Athens as well, because of course Athens jumps onto this fiscal bandwagon, and the Athenian Drachma, the silver stamped with the owl, becomes the currency that dominates the Mediterranean and does so for the next several 100 years.

AA: It's the Dollar of the day then, right?

JF: Absolutely it's the Dollar of the day. Which throws up some really interesting points.

I think some of the most fascinating things in the exhibition are two objects in the Panagyurishte Treasure. This is Bulgarian Thracian treasure made about 300 BC, after Athens has been conquered by the Kingdom of Macedon by Philip of Macedon, and then his son, Alexander, punches through and takes over the Persian world. Alexander the Great dies in Babylon in 323 BC and then – give or take a couple of decades after that, plus or minus a Thursday – this treasure gets made.

It is both Greek and Persian and it's part of this new international style of luxury that's Greek and Macedonian and Thracian and Anatolian and very, very Persian. And on two of the vessels, the libation dish and on an amphora rhyta, the two key vessels of this set of nine gold drinking vessels, each of them is inscribed with their weight, because they are there as bullion as well as luxury. They are there as portable wealth as much as they are anything else.

What I find fascinating is that the weight is given in two currencies, the Persian Daric and the Athenian Stater. And that shows us this moment of the transference, a sort of geopolitical shift in power, because this is very much the twilight of the Persian Daric and very much the dawn of the Athenian Stater, and the manufacturer of the Panagyurishte Treasure is hedging their bets. It's like, this would be the US Dollar and the Chinese Yuan, people are looking at both, thinking that one is on the way out and one is on the way in and you're seeing that in this inscription.

AA: The Panagyurishte Treasure, would that have been a gift to a client king maybe? It was discovered and dug up in a clay pit, right?

JF: Yeah, so the Panagyurishte Treasure – which we've borrowed from our colleagues at the National Museum of History in Sofia – it comprises 9 gold vessels, it weighs about 6.2 kilograms in total, and the gold is very pure, cut with a little bit of silver and copper, I assume for strength. I don't know if that's from the ore itself, but it's, you know, it's very high prestige stuff.

We don't know it's history, because three peasants, three labourers in 1949 called the Deykov brothers, turn up to work in an industrial clay pit, digging clay to make bricks at the local brick factory of the central Bulgarian township of Panagyurishte, hence the name of the treasure. The spades ring against a cache of treasure that's been hidden away, and initially they think they've discovered some musical instruments left behind by Romany travellers who had been in the area a little time before. Very quickly though they realise it isn't that actually. It was called at the time – and I think this still holds – one of the most significant archaeological discoveries made in Europe since the Second World War.

So I'll start at the end, and ask how did it get there? We don't know. This isn't a burial. But the Balkan Peninsula is very unstable around about 200 BC, when there's invading Celts, sort of Celtic tribesmen, coming into the vacuum left behind by the Hellenistic kingdoms before the Romans have come into being. And so we think whoever was owning the treasure at that point said to somebody, said to his steward, 'Right, go and hide this in the forest. Make sure you put up the marker stone. We'll go and get it when things settle down.' And no one does, of course, until the Deykov boys turn up in 1949.

How it was made is a different story. It was probably made around 300 BC. As I've said, we don't know by whom or for whom, but we can guess because the gold is so pure. The artisanship is so extraordinary, it is some of the best gold working you will ever see I think, certainly from the ancient world. And this speaks high prestige stuff. So my understanding – and I think this is the view shared by most scholars of this treasure – is that it was probably gold sourced in ancient Thrace, ancient Bulgaria by an ancient Thracian king, and he sent someone from his court with that gold, in the form of ingots if you like or the raw material, to a gold manufacturing centre. The most likely one is one of the cities on the Asian side of the Turkish Dardanelles, because they were really famous for their goldsmithing at this time, and it's probably being made to commission. 'Here's the raw material. This is the brief of what we want, we're after a set of nine drinking vessels, we want a libation dish, we want some rhytons. We want all of this. Make sure you put the weight on it too, because we're going to double check.' And then, of course, it goes back to the king.

Now, it might have been a gift. It might have been a diplomatic exchange. It might have been a simple commission, we don't know. But the person using it was almost certainly one of the Thracian kings, because it is superlative.

AA: Yes, it's fantastic. Just going back again to the Parthenon and this idea of storing wealth as a kind of collective value, even within this period it actually seems pretty unique to Athens? Because this wasn't happening with the Thracian king, this wasn't happening with the Persians. And this Greek idea of the communal storehouse, the Parthenon, there's a lot of touch points with, well, a lot of things in the more modern world.

I mean, the exhibition opened the same time as we had the coronation of King Charles, and of course the British – well, the English in particular – brought out all the magic spoons and the magic hats and the magic swords that can turn a prince into a king. It took a lot of gold, you need a lot of gold to turn a man into a king I discovered that weekend. And it's not dissimilar in the way that you've got this collectively owned treasure. At least that's the myth, that it is collectively owned. It's part of the state and the sovereign is serving the state and the state is us and we therefore are its owners. And the treasure gets brought out for special occasions. The Athenians used to parade it out of the Parthenon every so often, right, they used to literally carry it round the city on high days and holidays?

JF: Yes, and particularly for one religious festival, which is the Panathenaic festival which happened just one day every four years. They really turbocharged it so that everyone in the Attic peninsula would come in every four years for it, it was a seasonal thing. And you're right – people would dress up in their finery, and the entire populace, the demos, would parade through the city, the streets of the city of Athens, all the way up to the Acropolis and then ultimately, once it had been built in the 440s BC, the Parthenon. And the centrepiece, the focal point of the Parthenon, was a 12-metre high gold statue. A 12-metre high gold statue! That's a lot of gold, a statue of Athena Parthenos, the goddess herself in this environment, and she herself is bullion. I mean, you don't think of that as a gold statue of a god, you think of that as being sacred, and it was. But we know, I mean, Thucydides tells us that should the city need it for its defence, they could even melt that statue down as long as they'd made the requisite deals with the right gods, promising they would put it back when they were ready.

So there's a real commodification of stuff in this temple, and you're right: A lot of what was stored would be brought out and paraded through the streets as part of this Panathenaic procession. Not all of this was booty from the Persians. Some of it would have been, and those trophies would have been brought out as well, and you see this on some of the Parthenon reliefs, and we've got one of these slabs in the exhibition. It shows five maidens parading through the streets and they're holding Persian types of vessels, including what is probably a Persian silver incense burner. And I don't think these are generic 'Eastern style' stuff. I think these are very particular, I think these are vessels that are actually there in the Parthenon that are brought out every year so that people can see them and they're acting as trophies. They're reminding the Athenians about how they triumphed over the Persians and captured all their stuff.

This treasury was doing more than that though, because of course Athens by this point has emerged at the head of an empire of other Aegean city states, whether they want to or not. So by parading these luxurious trophies, Athens is also saying and it's making the argument that 'We have a right to rule you because we kept you safe during the Persian invasion. And look here, we've got all this stuff!'

It's also celebrating the wealth of the city, this is stuff that everyone can collectively draw on, should the city need it. So it's for the glorification of Athens itself.

AA: Not dissimilar then to a modern central-bank gold hoard, in a way? Currency reserves more broadly too – assets which are owned on behalf of the state on behalf of the demos for their protection in times of trouble?

JF: Yeah, absolutely. That's exactly what it is.

AA: I don't know if you've been to Nashville's Centennial Park or if you've got it planned, but you can see Athena Parthenos there in all her 12-metre glory.

https://www.nashvilleparthenon.com/collections

JF: Yes, I love the fact that in an exhibition on Persia to Greece I wrote a label about Nashville because, yes, the best reconstruction of the Parthenon, including the 12-metre high statue, is in Nashville, which is kind of wild.

AA: Really is. Now, all of this is two-and-a-half thousand years ago or more. What other echoes do you think there are in terms of today's attitudes and culture around luxury and power? Back to the exhibition's core themes you mentioned, about Persia kind of exerting its soft power through these displays of wealth and luxury, how does that echo today, do you think?

JF: In terms of that soft power, I think this exhibition is touching something that is fundamentally human and that is the way that states and rulers respond to each other through gifts. We could, and I was actually looking into it, we could have borrowed quite extensively from the [British] royal collections, because there are objects in there gifted to Queen Victoria by the Persian Shah, which could equally have been gifted to an Athenian diplomat by a Persian governor, a Persian satrap, and I think luxurious objects act as a kind of largesse in cementing political alliance and, well – that's very human.

But I also think that, in terms of the Athenian response to Persian luxury, we can hear or we can see the start of our own modern uneasiness towards luxury. And by that I mean, well, quite simply, we love to hate the Kardashians.

We see luxury as something to be very cynical about. We're very suspicious of its motives. We question it and yet we aspire to it. We embrace it. We want both sides of that luxury coin. And that is very much something that the Athenians are grappling with two-and-a-half-thousand years ago, because they're responding to all of this Persian stuff – the bullion, the metal vessels, all this sort of stuff. And they're saying 'This isn't us, we are simple and we're plain living and we're clean living and we're not tyrannical. And we'll put it in our Parthenon storehouse, and we own it collectively, all together. But individually, you know, we all look the same. You can't tell apart our slaves and our slave masters. We're all the same.'

That's the ideal, but of course in practise it was completely different, because of course people still respond to luxury and they take hold of Persian styles of luxury and twist it into sort of forms that make it acceptable. In ancient Athens, the one example I'll use is that of a parasol, because in Persia a parasol was the symbol of the king. The king was not supposed to have the rays of the sun touch his face, so he had a eunuch or an official holding a parasol above him, and it becomes a symbol of masculine regal power. Well, if you're an Athenian man, then to walk through the Athenian marketplace with a parasol, that is to reach for a power that you have no right to have. It's a very dangerous thing. However, this is a democracy where men can vote, but women have no power. So parasols get picked up, there's a stickiness to this eastern exotica that they still want, they still aspire to, but they bring it into the world of the feminine. This is the first time that parasols become a female item, and that's okay. They're neutered of any of their political potential or destabilising danger, because Athenian women have no political status. And in fact, it's kind of subverting that Persian leitmotif, if you like. And I think in that anxiety around luxury – that we both want it and we reject it at the same time – I think that is something that is fundamentally modern.

AA: I think we know what your favourite exhibit is, the Panagyurishte Treasure?

JF: Without the shadow of a doubt.

AA: Okay, but everything in the exhibition Luxury and power is priceless, and it would be a discussion for another day to talk about the idea of, you know, quite what price would the Panagyurishte Treasure fetch on the open market, because it wouldn't be an open market...

JF: Right...

AA: But in terms of historical value, you say it's perhaps the most important discovery in Europe since the Second World War. Is there anything else that stands out for you in terms of historical value? You know, what's the most priceless object? he said, ridiculously.

JF: Huh, interesting question! Let me give you an answer to that. I'll give you the priciest object in terms of its weight and also in terms of its historical resonance. This object does both, and it comes in a very quiet, unassuming little case in which we're talking about the colour purple.

Purple doesn't occur very often in the ancient world, and in the ancient Persian Empire, the Phoenicians are a group of people on the coast of southern Syria and Lebanon, and they've worked out that if you exude a mucus from the gland of a particular type of sea snail, and if you then expose that mucus to sunlight, you can turn it purple, this weird colour that people haven't really seen before.

AA: Oh man, how did people find this stuff out?

JF: Right, what did Samuel Johnson say? 'It took a brave man to taste the first oyster!' So who knows? But they worked out the recipe, and they keep it very secret. And so they refine that mucus, they dry it and grind it into a powder, and the Achaemenid kings give the Phoenicians a good tax break as long as they trade the purple at reasonable rates with the Persian Empire. Because purple becomes a sign of kingship, it's the ultimate form of luxury par excellence.

AA: It was still the imperial colour in Rome, right, and in the Catholic Church?

JF: Yeah, and this is the origin of that moment. It gets picked up by the Romans, it gets picked up in the ecclesiastical world, and there it is again at Charles' coronation, the velvet of the crown is purple. It goes back to this moment, it has that deep historicity about it, and it's going back to this manufacture of snail slime in the East Mediterranean. And in the exhibition we've got some purple powdered pigment. There's a guy in Tunisia – which is where the Phoenicians settled in North Africa, so we still get it happening there – and he's manufacturing this today using these ancient methods. We bought some off him and we've displayed that pigment and, by weight, by gram, that's more expensive than gold. It's more expensive than gold now, and it was more expensive than gold then, because it's so rare and so exotic, and it's absolutely fused to the concept of power. This is luxury and power on steroids. And I love the fact that it starts by squeezing a snail's mucus gland to get the slime out.

AA: That is fantastic, Jamie, and I think that just about wraps it up. Thank you so much for your time, and for your insights.

JF: Thank you.